By David "Chet" Williamson Sneade

He

was one of Worcester’s finest writers and close friends with America’s most popular composer. S.N. Behrman was the scribe. George Gershwin was the tunesmith.

According

to accompanying notes to his early biography, The Worcester Account,

the writer was born Samuel Nathaniel Behrman (1893-1973), “the son

of Jewish Lithuanian immigrants, was born in Worcester, Massachusetts

and grew up in a triple-decker at #31 Providence Street. His father

was a grocer and a Talmudic scholar who taught Hebrew to neighborhood

children. In Worcester, Behrman attended Providence Street School,

Classical High School, and Clark University.”

The

writer earned degrees from Harvard and Columbia before embarking on a

prolific and successful writing career that produced 30 plays, six

books of fiction and non-fiction, more than 20 filmscripts, and

countless newspaper and magazine articles.

Here’s

the writer from The Worcester Account: “We lived,

when I was a child and until I left Worcester, in a triple-decker

tenement a quarter way up the long hill that was Providence Street.

The street belonged to a few Irish, to a few Poles, and to us... .

These triple-deckers, which straggled up our hill, were mostly sadly

in need of paint jobs and their mass appearance was somewhat

depressing. But in the many other respects they were not so bad.

They had balconies, front and back, which we called piazzas.

“The

yards in the back had fruit trees – cherry and pear and apple. …

Once, standing on our back piazza, I overheard my young cousin, then

about eleven – my family, including my grandmother and two aunts,

occupied three of the six flats at 31 – improvising an ode to one

of the blossoming pear trees: ‘Oh, you elegant tree!’ she began.

But then she caught my eye and the rhapsody was aborted. The

contemplative and withdrawn could sit on the back piazzas and look at

the fruit trees; the urban and the worldly could sit on the front

piazza and survey the passing scene.”

|

| Water Street, Worcester |

Gershwin

biographies are many. He was born in Brooklyn, New York on September

26, 1898, the second son of Russian immigrants. The 5-cent take

on Gershwin's life is that he dropped out of school at the age of 15 to

become a piano-playing song-plugger on Tin Pan Alley. According to

biography.com, “Within a few years, he was one of the most sought

after musicians in America. A composer of jazz, opera and popular

songs for stage and screen, many of his works are now standards.

Gershwin died immediately following brain surgery on July 11, 1937,

at the age 38.”

Gershwin

often spoke of the melting-pot-ideal of America. In

1927 he was quoted as saying, “Wherever I went I heard a concourse of

sounds. Many of them were not audible to my companions, for I was

hearing them in memory. Strains from the latest concert, the cracked

tones of a hurdy-gurdy, the wail of a street singer to the obligato

of a broken violin, past or present music, I was hearing within me.

Old music and new music, forgotten melodies and the craze of the

moments, bits of opera, Russian folk songs, Spanish ballads,

chansons, ragtime ditties, combined in an inner chorus in my inner

ear. And through and over it all, faint at first, loud and fast, the

soul of this great America of ours.”

In

the early part of the 20th century jazz was very much a

part of that equation and Gershwin loved the music. “There had been so much chatter about the

limitations of jazz,” he said in the wake of his masterpiece,

Rhapsody in Blue, which opened the doors of concert halls to popular

music. “I resolved, if possible, to kill that misconception with

one sturdy blow. … No set plan was in my mind – no structure to

which my music would conform. The rhapsody, as you see, began as a

purpose, not as a plan.”

For

more on Gershwin’s life see:

www.biography.com/people/george-gershwin-9309643

Behrman

first met Gershwin when the two men were both in their early twenties.

David Ewen, in his book George Gershwin; His Journey to Greatness,

states: “Among the new faces in the Gershwin circle in the early

1920s was S.N. Behrman – “Bernie” to his friends – who, in

1923, was writing for The New York Times Book Review and

various magazines.

+S.N.+Behrman.jpg) |

| The Gershwin circle of friends. The composer is front and center. The writer is top and center. |

“Behrman

had been initiated into the theater in his youth when he appeared in

a vaudeville sketch of his own writing. But it was not until 1927

that he emerged as a leading playwright of social comedy when the

Theater Guild produced The Second Man. Thus Behrman and

Gershwin – who were introduced to each other by Samuel Chotzinoff –

became friends before either were famous. As each progressed from one

triumph to another, each remained close to the other.”

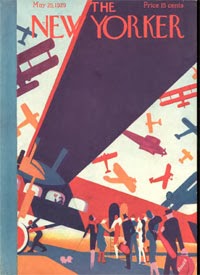

Behrman

wrote about his friend on several occasions. First was the writer’s

debut as a “Profile” columnist for The New Yorker. The

piece is called “Troubadour,” originally published in the May 25, 1929

edition of the magazine.

Among

the many facts, insights, and tales Behrman relates to readers about

his friend is his piano playing: “Because I have no authority to

write about music, I have spoken with circumspection of Gershwin's

achievements as a composer. I come now to a side of his talent of

which I can speak because I have been under its spell—his immediate

talent as a pianist, as an interpreter of his own songs.

“Josef

Hofmann says of Gershwin that he has 'a fine pianistic talent .

. . firm, clear . . . good command over the keyboard.' To the

layman it seems a positive domination. You get the sense of a

complete mastery, a complete authority—the most satisfactory

feeling any artist can give you. When he sits at the piano and plays

his own songs in a roomful of people, the effect that he evokes is

extraordinary. I have seen Kreisler, Zimbalist, Auer, and Heifetz

caught up in the heady surf that inundates a room the moment he

strikes a chord. It is a feat not only of technique but of sheer

virtuosity of personality.”

See more of piece at: http://snbehrman.com/library/newyorker/29.5.25.NY.htm

Behrman

wrote more extensively about Gershwin in his book, People in a

Diary; A Memoir. In the chapter, “The Gershwin Years,” he

expounds on the piano playing, saying, “I have read numberless

pages of musical analysis of Gershwin songs and his more ambitious

writings by experts – ‘diminished sevenths,’ ‘tonic triads,’

‘broken chords.’

“I

don’t understand any of it as I know nothing about music.

Gershwin’s originality, they all agree, came from his intuition for

the dramatic and the colloquial. But when I first heard him, and

subsequently, I found that I had an intuition of my own – as a

listener. I felt on the instant, when he sat down to play, the

newness, the humor, above all the rush of the great heady surf of

vitality. The room became freshly oxygenated; everybody felt it,

everybody breathed it.”

In

that same chapter, Behrman covers all things Gershwin, including, the man,

the pianist, the composer, friendship, psychoanalysis, his brother,

Ira; family, death and his legacy. “Thinking back on George’s

career now,” he recalls, “I see that he lived all his life in

youth. He was thirty-nine when he died. He was given no time for the

middle years, for the era when you look back, when you reflect, when

you regret. His rhythms were the pulsations of youth; he reanimated

them in those much older than he was. He reanimates them still.”

Behrman

never collaborated with Gershwin. He did however use one of the

composer’s tunes in the play about his friend and the lost

generation of the youth. The tune is called, “Hi-Ho,” an obscure

song that Gershwin first introduced in the musical, Shall

We Dance,

but was cut.

According

to Walter Rimler, “The

song was first heard publicly in the late 1940s in an S.N. Behrman

play, Let

Me Hear the Melody,

which was based on the author's memories of George Gershwin and F.

Scott Fitzgerald. But the play and the song went nowhere. Publication

did not come until 1967, when the composition was made part of an

exhibition of Gershwin works at the Museum of the City of New York.”

It

is not known whether or not Gershwin and Behrman were ever in this city at the

same time. Gershwin did appear in town at the Worcester Memorial Auditorium

with singer James Melton and the Leo Reisman Orchestra on Tuesday,

January 16, 1934.

The concert was reviewed by Dorothy Boyd Mattison for the Worcester Daily Telegram. “Chief attention doubtless centered upon Mr. Gershwin’s playing of his own ‘Rhapsody in Blue,’ for which the current tour marks the 10th anniversary of its composition, his ‘Concerto in F,’ which opened the program, and his tone poem, ‘An American in Paris.’

The concert was reviewed by Dorothy Boyd Mattison for the Worcester Daily Telegram. “Chief attention doubtless centered upon Mr. Gershwin’s playing of his own ‘Rhapsody in Blue,’ for which the current tour marks the 10th anniversary of its composition, his ‘Concerto in F,’ which opened the program, and his tone poem, ‘An American in Paris.’

“Probably the most delightful moment of the program came at the very end when Mr. Melton and Mr. Gershwin, tossing aside the final scheduled number, ‘Wintergreen for President,’ and silencing the orchestra, got together at the piano. Mr. Gershwin played and Mr. Melton sang ‘Of Thee I Sing’ and a number from Mr. Gershwin’s ‘Oh, Kay!’ The informal, parlor-like atmosphere lent zest to the evening, and brought it to a beautiful climax.”

Behrman

noted that after Gershwin died fellow friend, Fred Astaire said, “He

wrote for feet.” The writer adds, “A Gershwin tune has a

propulsive effect still, all over the world.

He was perpetually in pursuit of new horizons; he was ambitious to write serious music. In youth there is always time for everything; we all aged; George remained young. His own tempo was as propulsive as those of his songs …."

He was perpetually in pursuit of new horizons; he was ambitious to write serious music. In youth there is always time for everything; we all aged; George remained young. His own tempo was as propulsive as those of his songs …."

Reflecting and ruminating further about his friend in his memoir, Behrman writes: “One can never know the truth about anyone – what their inmost motivations and feelings are, but George’s life was lived so out-of-doors, so in the public eye, and these activities so absorbed him that he was always ‘too busy,’ he said, for introspective agonies.

"He told me once that he wanted to write for young girls sitting on fire escapes on hot summer nights in New York and dreaming of love. His memory is of a golden youth, of a young man who in a short time won all the rewards of acknowledged genius.”

Thank you.

Resources

http://books.google.com/books?id=RySwdc151ZoC&pg=PA705&lpg=PA705&dq=Gershwin+and+S.N.+Behrman&source=bl&ots=SJRmKAkqRl&sig=XJxFiq4j_c7mS8JFgtPTwROR3ro&hl=en&sa=X&ei=KcDFUtGXGIPOyAGg9IDICw&ved=0CEEQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=Gershwin%20and%20S.N.%20Behrman&f=false

http://books.google.com/books?id=wCPPPHM44sIC&pg=PA320&lpg=PA320&dq=Gershwin+and+S.N.+Behrman&source=bl&ots=YpEikShid-&sig=ShSra2epynBeP39Dx_lVVbxH4T0&hl=en&sa=X&ei=KcDFUtGXGIPOyAGg9IDICw&ved=0CFMQ6AEwBw#v=onepage&q=Gershwin%20and%20S.N.%20Behrman&f=false

http://books.google.com/books?id=azDngIN8cBcC&pg=PA32&lpg=PA32&dq=S.N.+Behrman+and+jazz&source=bl&ots=NxcIm1v3Ek&sig=c-v2wTiiEc4fJFzfUeQsQpuAN1A&hl=en&sa=X&ei=WsHFUtvOGIjQ2AWhs4DgDA&ved=0CEoQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=S.N.%20Behrman%20and%20jazz&f=false

http://books.google.com/books?id=a0urqvDSAS4C&pg=PA166&lpg=PA166&dq=s.n.+behrman+and+jazz&source=bl&ots=yiVKEzoLNp&sig=gG0WdoeynzgXM8wuSAh6j8ffPTw&hl=en&sa=X&ei=HGbIUrKqGrKqsAT6roCQDw&ved=0CCsQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q=s.n.%20behrman%20and%20jazz&f=false

http://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/07/nyregion/about-new-york-rhapsody-in-bohemia-cookies-and-gershwins.html

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)