By David "Chet" Williamson Sneade

It’s

common knowledge that in addition to being a famous jazz trumpeter, Chet Baker

was also a notorious junkie.

Many of his drug-addled days were littered with tall tales shrouded in myth, even in death. He died tragically as a result of falling out of a window in 1988.

Many of his drug-addled days were littered with tall tales shrouded in myth, even in death. He died tragically as a result of falling out of a window in 1988.

One of

the more unusual stories of Baker’s dope chasing happened in Worcester

The account is documented in James Gavin’s biography, Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker.

The account is documented in James Gavin’s biography, Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker.

Evidently, for years Baker and fellow musician Gerry Mulligan were under constant surveillance and

harassment of John Edward O’Grady, head of the narcotics bureau of Hollywood Hollywood

According

to Gavin, O’Grady amassed what some called the biggest narcotics arrest in

history in the LAPD history: an estimated 2,500-plus suspected junkies and

pushers, many innocent. His main targets were jazz musicians, whom he

considered, “the dregs of society.”

In his

book, O’Grady bragged, “I set out to destroy that crowd and damn near did…. I

ran Charlie ‘Yardbird’ Parker, the great saxophonist, out of town. I could have

nailed him. His arms were covered with track marks from heroin needles. But he

was too old and too drunk and I decided it wasn’t worth wasting the time

nailing Parker just so the City of LA

Gavin

asserts that also on O’Grady’s hit list of arrest targets were the likes of

Stan Getz, Billie Holiday, Lenny Bruce, as well as Mulligan and Baker. “It

turned into a plague,” Mulligan is quoted as saying. “O’Grady used to love to

come around and bait Chet, and Chet always had a smart rejoinder so this guy

was after him.”

On April

13, 1953 ,

Mulligan, Baker and their wives at the time were in fact busted. While the

musicians were plying their trade at the Haig on Wiltshire Boulevard Hollywood

The

account is well documented in Gavin’s book and elsewhere. The detectives didn’t

find any hard drugs, only marijuana. They then proceeded to the club and confronted

the musicians backstage, ordering them to roll up their sleeves. “Look at that

– fresh marks,” O’Grady is reported to have said. At this point, they drove

back to the house in search of drugs. Mulligan relented and presented them with

the evidence, his works [needles] and a small amount of heroin.

The

headline read: “Hot Lips Bopster, Aide and 2 Wives Jailed; Nab Dope.” Mulligan

spent six months in jail at Sheriff’s Honor Farm in Modesto

Two years

onward, Baker had had enough. Gavin: “In 1955, on a trip to Worcester , Massachusetts

A word on

Loughborough: Commonly known as Bill Love, he passed away on April

7, 2010 .

He was a cat of many lives and one who resided in and out of the jazz purview.

In music he is best known as the co-author, along with David “Buck” Wheat, of

“Better Than Anything,” a popular jazz number covered by numerous artists

including, Irene Kral, Sheila Jordan, Bob Dorough, and Al Jarreau.

Wheat and

Loughborough grew up together in San Antonio , Texas

A

one-time 16 year-old student at MIT, Loughborough was a life-long advocate for the disabled. For more on this fascinating character of America

For more

on Partch see: http://www.harrypartch.com/

The question

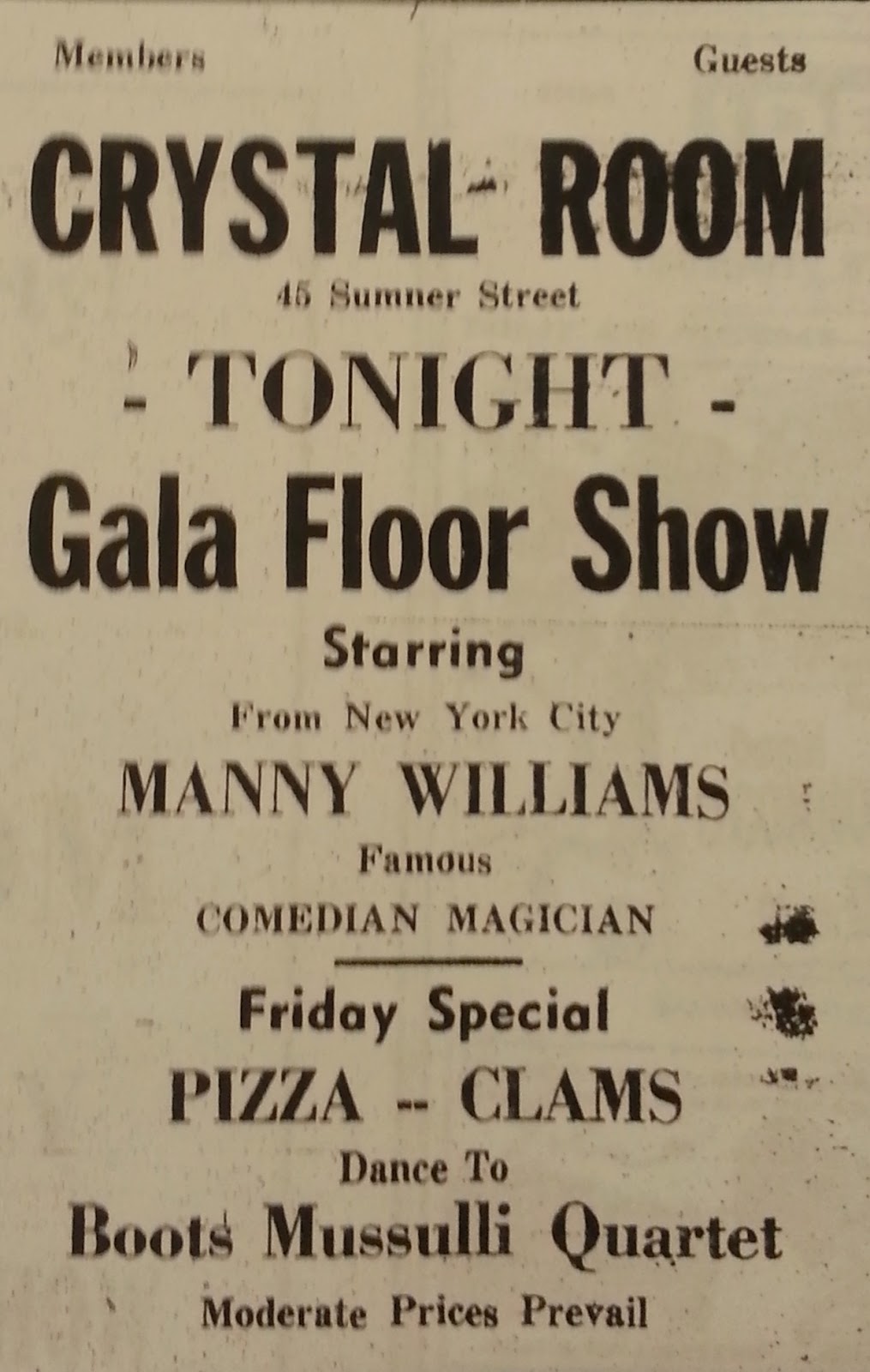

is: What was Loughborough and Baker doing in Worcester

Also, the

Baker band was touring the East Coast that summer appearing at such places

as the Newport Jazz Festival and the Celebrity Club in

Also, the

Baker band was touring the East Coast that summer appearing at such places

as the Newport Jazz Festival and the Celebrity Club in  The pianist in the band had

other reasons to visit

The pianist in the band had

other reasons to visit Freeman worked with Baker from the summer of 1953 through August 1955. The pianist is quoted as saying that the trumpeter's heroin use began at the end of 1954. "He started to use right around the time everyone else was stopping. Drugs were going out of fashion. I was also strung out for a time, but I had stopped just when we started the quartet in June of 1953. Chet was also the only guy who continued so long while other junkies either quit or died."

In 1955, Chet Baker was deep into the throes of junkiedom. Before the year was out, the brilliant young pianist Dick Twardzik, who was touring

For

more on Twardzik, see: http://www.jazz.com/jazz-blog/2009/1/20/twardzik-chambers-one

|

| Pianist Dick Twardzik in action as a ghostly Chet Baker looks on |

As far as the location of the

Gypsies? Documented

histories of such people who lived or traveled in and around Worcester

Although,

in this bizarre midnight ritual Baker was convinced by the performance of the

men and the authenticity of their supernatural powers.

“Years

later,” the trumpeter claimed that the curse had worked,” Gavin reported, “not

only had O’Grady been ejected from the narcotics squad, but Baker heard,

had been badly injured by a bottle thrown at his head.”

|

| Chet Baker at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1955 |

Note: This is a work in

progress. Comments, corrections, and suggestions are always welcome at: walnutharmonicas@gmail.com. Also see: www.worcestersongs.blogspot.com Thank you.

.jpg)