By David "Chet" Williamson Sneade

There

has been an ocean of words written by and about poet Charles Olson.

Here are a few hundred more water spots, scribbles, and ink stains.

The specific focus of this piece is the influence jazz had on both

his writing and reading style.

Born

in Worcester in 1910, Olson is considered a giant (literally and

figuratively – he was six feet, eight inches tall) among American

poets. The man who is said to have coined the expression,

“post-modern,” Olson is recognized as a second generation

modernist who reaches back to seminal, first generation poets such as

Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, and T.S. Eliot. His

work extends forward to reach deep into the new American poetry of

the last half of the 20th century as well.

According

to Poets.org, Olson was the son of Karl Joseph Olson – who was a

postman in the city -- and Mary Hines. Charles Olson received his BA

and MA from Wesleyan University before teaching English at Clark

University. Two years later, he entered Harvard University in 1936,

where he completed coursework for a PhD in American civilization.

“By

the age of twenty-nine, he had received his first Guggenheim

fellowship for his studies of Herman Melville,” the site reported.

“Rather than pursuing an academic career, Olson became active in

depression-era politics. He served as the assistant chief of the

foreign language section of the Office of War Information (OWI).”

|

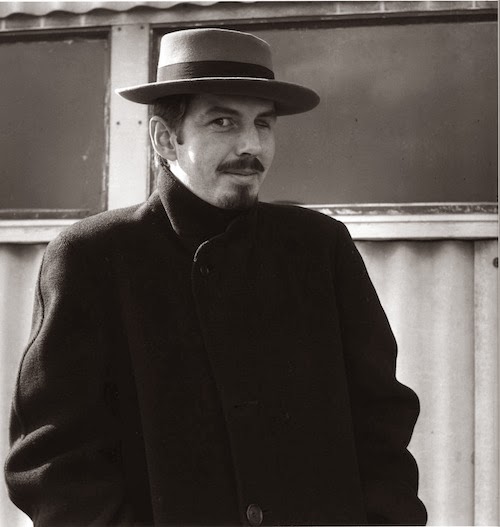

| Student Olson |

Disillusioned

over an issue of censorship, Olson quit the organization in 1944 to

dedicate his life to writing. In 1945, he moved to Key West, Florida

and did just that. In 1950, he published his influential

essay, "Projective Verse." “Among other things,”

Poets.org points out, “the essay posited that poetry should embody

the rhythms of natural breath and thought.”

Olson's

ideas on poetics – especially those of “projective verse” --

had a profound influence on a generation of poets, including Denise

Levertov, Paul Blackburn, Ed Dorn, Jonathan Williams, Robert Duncan

and Leroi Jones, among others.

First

written in 1950, it was later published by Amira Baraka (Leroi Jones)

as a pamphlet for Totem Press in 1959, Projective Verse is

literally Olson’s revolutionary manifesto on how to do poetry in

the post-modern world.

In

a reading at the Fourth Annual Charles Olson Memorial Lecture at the

Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester in 2013, Baraka read a piece called,

“Charles Olson and Sun Ra – A Note on Being Out.” “If you

cannot make the connection that is between Olson and Sun Ra, you

cannot understand the topology of that time,” he said. “This

essay changed the direction of many young poets writing in the U.S.

in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Olson urges the poet to stop using the

closed forms of the formal U.S. verse … particularly, stop

using the dead inherited detritus of the English poetry – that a

new American poetry must be built on the ear, the breath, the sound

of the poet. It would be composition by feel, rather than overused

inherited, largely academic, usually iambic form.”

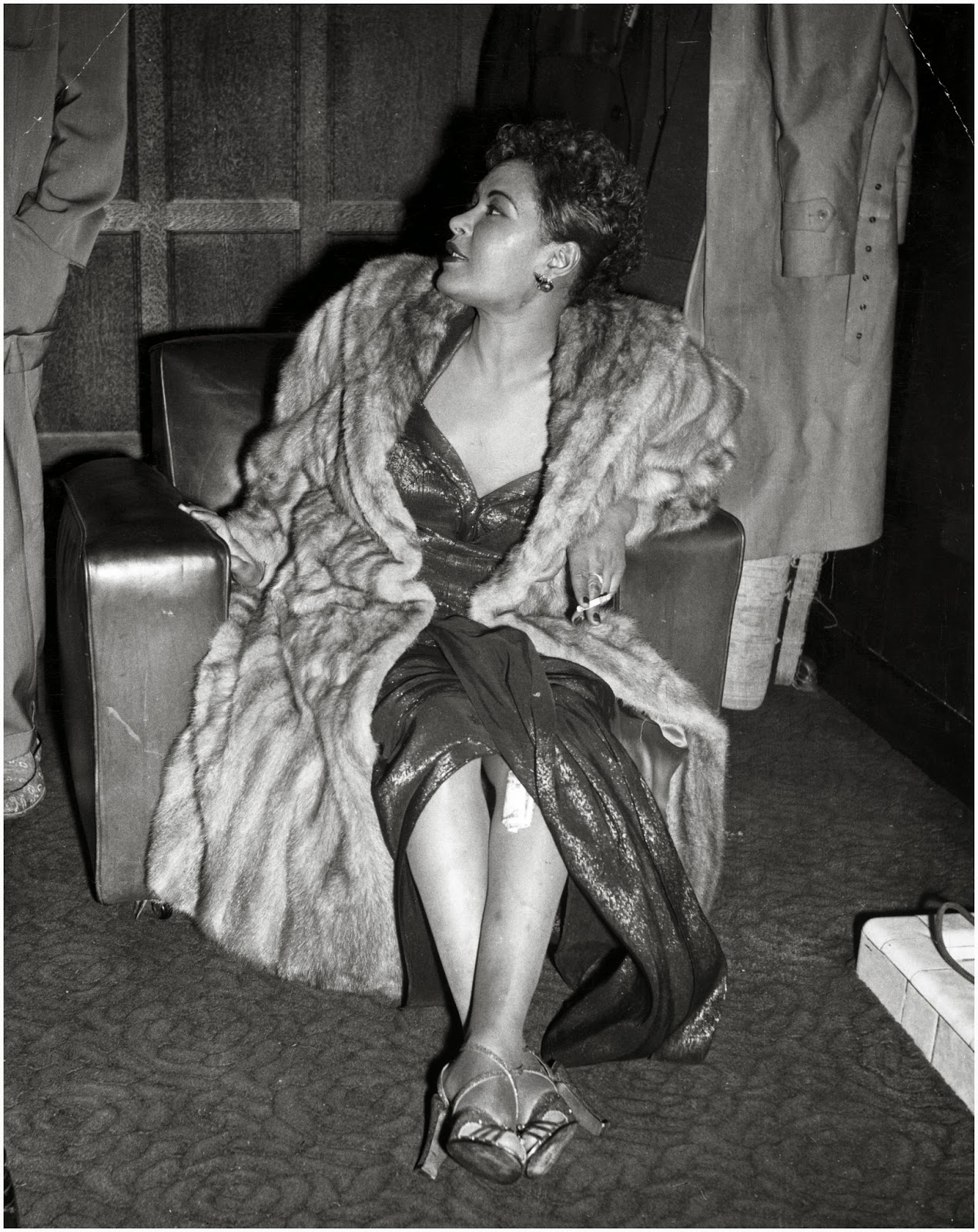

|

| Baraka |

In 1950, the year that Olson writes Projective Verse, Herman “Sonny” Blount changes his name to Sun Ra, after the ancient Egyptian sun god. Speaking of Ra and his mystical, magic music, Baraka says, “The parallel that tie Olson and Ra -- they both exert great influence over American art during the ‘50s until this day.”

|

| Sun Ra, looking radiant |

|

| Herman "Sonny" Blount, AKA Sun RA |

Very

much inspired by jazz and the bebop that he listened in the 1940s,

Olson was once asked to describe the poetic theory. “Boy, there was

no poetic,” he cracked. “It was Charlie Parker. Literally, it was

Charlie Parker.”

Still,

in Projective Verse, he spells it out: “First, some

simplicities that a man learns, if he works in OPEN, or what can also

be called COMPOSITION BY FIELD, as opposed to inherited line, stanza,

over-all form, what is the “old” base of the non-projective.”

Riffing

more deeply, Olson explains, “Then the poem itself must, at all

points, be a high-energy construct and, at all points, an

energy-discharge.” He then states, the essential principle of

projective verse. “It

is this: FORM IS NEVER MORE THAN AN EXTENSION OF CONTENT.”

In

1951, Olson was hired to teach at the progressively minded, Black

Mountain College, North Carolina. Poet Robert Creeley, who would

become a life-long friend of Olson’s, was a student at the school.

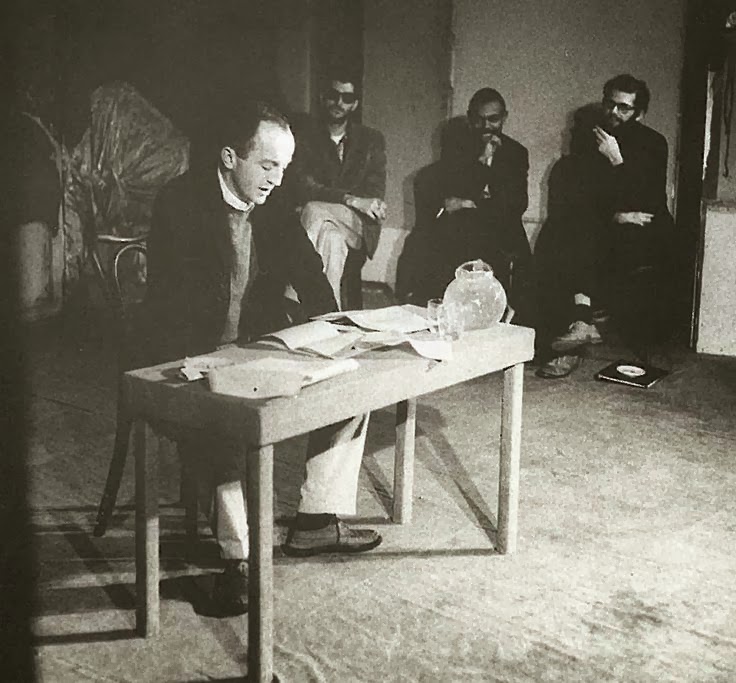

|

| Robert Creeley |

Olson

credits Robert Creeley with giving him the line of: “Form is never

more than an extension of content.” In an interview with the Poetry

Foundation, Creeley explained Olson’s projective voice stating:

“What he is trying to say is that the heart is a basic instance not

only of rhythm, but it is the base of the measure of rhythms for all

men in the way heartbeat is like the metronome in their whole system.

“So

that when [Olson] says the heart by way of the breath to the line, he

is trying to say that it is in the line that the basic rhythmic

scoring takes place. . . . Now, the head, the intelligence by way of

the ear to the syllable – which he calls also 'the king and pin'—

is the unit upon which all builds. The heart, then, stands, as the

primary feeling term. The head, in contrast, is discriminating. It is

discriminating by way of what it hears."

Creeley,

who was born in Arlington and raised in Acton, MA, dropped out of Harvard and began hanging out in Boston jazz clubs like the Hi-Hat to

listen to musicians, who would become the major influence on his

poetry. He would later release two albums on the ECM label with jazz

bassist Steve Swallow, Home and So There.

In

his book, The Culture of Spontaneity: Improvisation and Arts in

Post War America, author Daniel Belgrad states: “In 1950,

Robert Creeley wrote Charles Olson a letter pointing out the

correlations between Olson’s projective first essay in modern jazz.

Creeley wrote that Charlie Parker, Max Roach, Miles Davis, and Bud

Powell were undertaking extensions of form analogous to those that

Olson was proposing in verse.

“In

particular, he singled out bebop’s sensitivity to rhythm and tone:

‘Some notes on the thing about the project verse … Two things we

have yet to pick up on, with the head: a feel for timing, a feel for

SOUND.’ Creeley praised bebop as embodying a counter-cultural

sensibility, calling it an example, of ‘what timing variation, and

sound-sense can complete … a precise example of a consciousness

necessary.’”

|

| Charlie Parker and Miles Davis |

In

an interview conducted by Chris Funkhauser, the writer asked pianist

Cecil Taylor, when he engages with poetry, if he was influenced by the

concept of open verse. “I would say that it is difficult,” Taylor

answered. “Do you know Creeley's book, The Island? Well, I

read that. The thing-- Olson, Charles Olson might be easier to talk

about, or Bob Kaufman, but the thing that allows me to enter into

what they do is the feeling that I get.

|

| Cecil Taylor |

“It's

the way they use words. It's the phraseology that they use, much the

way the defining characteristic of men like Charlie Parker or Johnny

Hodges is the phraseology. And in the phraseology would be the

horizontal as well as the vertical. In other words, the harmony and

the melodic,” Creeley said.

|

| Charles Olson in the classroom |

At

its fundamental, Olson talks about “certain laws and possibilities

of the breath, of the breathing of the man who writes as well as of

his listenings.” He also explains that the ideas of projective

verse is about the “process” rather than the “product.”

Therefore, spontaneity, action, and energy replace reasoning and

description in the conception of a poem. Ultimately, find your own

line breaks according to your own breath.

In person, at readings, Olson was larger-than-ordinary-life. Anne Waldman recalls seeing him at the Berkeley Poetry Conference in 1965. “It was incredible to watch a poet seemingly enact his

whole life – from infancy to old age – up there in front of you; very scary, but also moving, profound, and vulnerable. Up there

without props, without a script, every idea of text or presentation

tossed to the win. Probably inebriated, not giving you any sort of

line, not dishing out some message or propaganda, but just opening up

his head in public.”

Here is his poem, Sing, Mister, Sing:

Hills are grey elephants

the sun is a prince

the plains is an ocean

Bigmans pants

pound the earth, pound the earth

I dance, I dance

The prince is astride

the grey hills glide

the ocean's a tide

Bigmans hide

round the earth, round the earth

I ride, I ride

Ride and prance

brag and dance

round the world, round the world

Bigmans chance

Here is his poem, Sing, Mister, Sing:

Hills are grey elephants

the sun is a prince

the plains is an ocean

Bigmans pants

pound the earth, pound the earth

I dance, I dance

The prince is astride

the grey hills glide

the ocean's a tide

Bigmans hide

round the earth, round the earth

I ride, I ride

Ride and prance

brag and dance

round the world, round the world

Bigmans chance

After

the Black Mountain College closed in 1956, Olson taught at State

University of New York and the University of Connecticut. He settled

in Gloucester, where his family spent their summers for most of

Olson’s childhood. He died of liver cancer in 1970.

Thank

you.

Resources

http://books.google.com/books?id=T-TkNOeTtc8C&pg=PA139&lpg=PA139&dq=charles+olson+and+Amiri+Baraka&source=bl&ots=8Pr6FTuC72&sig=lsQqsurUttSmH7JC0-YERhed8e8&hl=en&sa=X&ei=gsfhUuDVD6eh2AX6soDACw&ved=0CCYQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q=charles%20olson%20and%20Amiri%20Baraka&f=false

http://books.google.com/books?id=D2e8x_0AwokC&pg=PA75&lpg=PA75&dq=charles+olson+charlie+parker&source=bl&ots=3wg5mOaGVx&sig=8Ont7ng_OGd0p3afjyrjKfOtGBc&hl=en&sa=X&ei=FrbhUuTzA4HZrgGI_oGYCg&ved=0CDUQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=charles%20olson%20charlie%20parker&f=false

.jpg)