By David "Chet" Williamson Sneade

|

| The Boots Mussulli Quartet, live at the Fox |

The reel

to reel tape had been sitting in Richie Camuso’s dresser drawer for

more than 40 years. For local jazz fans, the rediscovery of the Boots Mussulli Quartet live

at the Fox Lounge is something akin to the finding of a long lost performance

of Charlie Parker. It’s that significant.

First of

all, it is the only known sound document of the group. In its nearly 10 years

of existence the quartet never formally recorded. This was a home recording set

up with one mike in the middle of the club on Rte. 9 in Westborough. By most

accounts it was a Sunday afternoon session in 1964.

Known as

“The Music Man of Milford,” Mussulli was a

legendary figure in the annals of local jazz history. He was a brilliant

saxophonist, who toured with the likes of Charlie Ventura, Gene

Krupa, and Stan Kenton. It was Mussulli who set the standard for alto greatness in

the Kenton band. He

preceded Art Pepper, Lee Konitz, Lennie Niehaus, Bud

Shank and Charlie Mariano.

For his

effortless mastery of the instrument, Mussulli was

recognized as one of the finest alto players in the world. At one point in the

late ’40s, Charlie Parker was voted No. 1 and Mussulli No. 2 in Downbeat Magazine’s prestigious

musician’s poll.

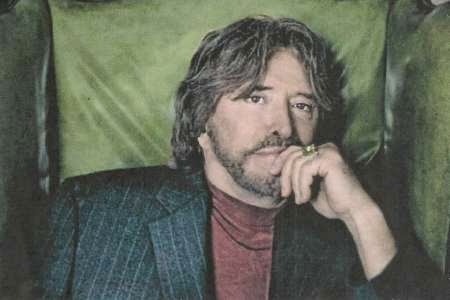

|

| Enrico "Boots" Mussulli |

After

pulling off the road in the early 1950s, Mussulli set

up shop as a teacher, opening a music studio in an office building in downtown Milford, “Room 18” at 189 Main Street. His teaching left an

unparalleled legacy. A partial list of those who studied with Boots includes

such notable players as drummers Frankie Capp and Bob Tamagni, trumpeters Don Fagerquist and John Dearth, trombonists Tony Lada and Gary Valente and saxophonists Jackie Stevens, Bill

Garcia, Tom Herbert and Ken Sawyer.

In

addition to teaching, Mussulli conducted the Youth Orchestra of Milford, a

big band consisting of players who ranged in age from 11 to 19. In July of

1967, the orchestra was featured at the Newport Jazz Festival on a

bill with Dave Brubeck, Duke Ellington and Sarah Vaughan.

Mussulli

would also take an occasional short tour with Boston-based musicians Herb Pomeroy and Serge Chaloff, both of which had recorded great sides with Boots for

Capitol. At home, his working quartet featured pianist Danny Camacho,

bassist Joe Holovnia and drummer Arthur Andrade.

The tape

captures the band in great form at the height of their prowess. Each player is

given plenty of room to shine and that they do — covering standards, originals

and bebop classics. Clocking in at more than 75 minutes, the tape, which has

been converted to CD, includes, “You Stepped Out of a Dream,” “Rhythm &

Boots” (Mussulli), “Polka Dots and Moonbeams,” “My Funny Valentine,” “Parker’s

Blues” (Mussulli), “Desafinado,” “Lullaby in Rhythm,” “You Can’t Take That Away

From Me,” “Confirmation,” “My Old Flame,” “It Might As Well Be Spring,” and “I’ll

Remember April.”

“I was

studying saxophone with Boots at the time,” says Camuso. “I got to be very

friendly with him. I used to help him with the Youth Band. We decided to try

and do a live thing. It was between Boots and I that we set up everything.”

Camuso,

who plays tenor saxophone for his own enjoyment, is no stranger to local jazz

fans. For many years he was a programmer at WICN. “At that time there were no

cassettes,” Camuso says. “That was one of those reel to reel tapes. It was like

a small suitcase. I think we only had one mike for the whole group -- most of

the time it was in front of Boots. He would pick it up and bring it over to the

piano when Danny was doing a solo. We did shut it off in between numbers so we

could get as much music as we could on the tape, rather than have the tape

running just to hear the audience. It’s like the whole afternoon. They gigged

there from 3 to 7 p.m.

|

| Camacho and Holovnia |

Asked

about the group, Camuso says, “Joe Holovnia, who was Boots’ last bass player, he

was probably one of the best around. Danny, who lived in Framingham, he was a dynamite piano player. Once the CD was done I sent him a copy and we had a long conversation on the

phone. When he heard it, he said, ‘I never realized I could play that fast.’

Arthur Andrade was one of the most underrated drummers around in his time.”

After

making the tape, Camuso says he used it for a while as a teaching tool before

putting it away all these years. Fearing it would disintegrate, he finally

pulled it out hoping it could be salvaged. Camuso brought the reel to reel tape

to Vince Lombardi, executive director of Audio Journal, who had the

equipment to transfer the music to compact disc.

|

| Vince Lombardi |

“I

figured once I played it, the thing would crumble up,” Camuso says. “You should

have heard the tape. We thought it was good at the time, but the sound is lousy

in comparison to today. The music technology wasn’t there in those days. Vince

did a great job. It’s a thrill for me.”

“Richie just gave the tape to me

raw,” Lombardi says. “He had this little treasure for years and had no way of

listening to it. Some of it we couldn’t even use. The leader was kind of

crinkled. The first step was to get it from that tape and record that into our

production computer. Then there is an audio editing type program that we used,

called ‘Cool Edit Pro.’

“I didn’t

want to ‘studio’ it out, filter it out. I couldn’t tell you exactly how it

happened but I fiddled with it until I could eliminate some of the hiss and boost

the bass up a little bit -- tweak it as much as I had the capacity to do. We

cut a lot of the crowd noise out. I’m not positive, but I think we lost maybe a

tune and there was a limitation on how much we could put on one disc.”

Lombardi

says though it is clearly marked “Fox Lounge” on the box, the date is a little

sketchy. So on the CD version, he lists it as ‘1960-something?’ Camuso provided

as much information as he could, including the personnel. As for the tunes, “I

don’t know if Boots announced any of the tunes,” he says. “I called different

people and asked, ‘What is this one? Joe Holovnia is a wealth of information,

having played with [Boots], he also helped me identify the tunes.”

Lombardi

provided the service gratis, saying it was gratifying for him that Audio

Journal was able to it. “We are trying to do more of this kind of service —

audio production, commercial service. This was a good indication that we have

the capacity to do that.”

In

addition to directing Audio Journal, Lombardi was a fill-in jazz host at WICN. After

mixing and downloading the music, he presented a sampling of the session in a

special presentation on the radio show “Jazz New England.” Between the

recording and presenting of the broadcast, Lombardi says he’s developed a

greater appreciation for Mussulli.

“He was

buried in the Stan Kenton recordings,” he says, “but then when we found this, I

realized what everybody was talking about. The recording also tells you how

even as good as Boots was the crowd took it for granted. They were talking.

They were noisy. We are in danger of doing that when we have a wonderful

musician in our midst.

“It’s

chronological. As the night wears on you can hear the people getting more and

more into it. It was kind of a busy, fun crowd. It’s like, ‘Oh, by the way,

what’s that great music going on in the background?’ I think it was an

interesting slice of history.”

Mussulli

died in 1967. Andrade is gone as well. For Camacho and Holovnia, the only surviving members of the group, the rediscovered recording is both a cause for celebration and

bittersweet reminder of better days gone by.

When

asked how he hooked up with Boots, he chuckles again and says, “Oh, that’s a

long story. I was playing locally. I’m originally from Hudson. I played quite a bit in Hudson. I started in my teens in local

bars -- Manny’s Cafe and all those type places in town.

|

| Pianist Comacho |

“Then I

got involved with a lot of musicians from Marlborough when I got into the local union.

Then it just spread out. I was fortunate to be able to play with these

musicians that were older than me. I got a lot out of it.

“Anyway,

I was playing a wedding with local musicians and Arthur Andrade was the

drummer. I had played with him for many years, since we were kids. He used to

play with his mother and father when he was a kid. He was no taller than his

bass drum. They used to play at the Portuguese Club in Hudson. They used to have dances there.

I was Portuguese myself and I lived in Hudson. I was born and brought up there.”

Continuing

the story of the Mussulli connection he says, “I was playing with Arthur and Al

Sibilio, a tenor sax player from Marlborough. We worked with him quite a bit.

We were playing at the VFW Hall in Marlborough. Frank Tamagni, the tenor

sax player from Milford, was there as a guest at the

wedding. Of course, he’s very good friends with Boots. I don’t know him from a

hole in the wall at the time. Anyway, we are playing and he comes up to me and

asks if I’d heard of Boots. I say, ‘Well I’ve heard of him, but I’ve never

played with him.’ He says that Boots was looking for a piano player.”

One of

the early gigs that the Boots Mussulli Quartet played was at Eddie

Curran’s Christy’s Restaurant on Rte. 9 in Framingham. In the early ’50s, the room

developed quite the reputation as a jazz haunt. In 1951, Charlie Parker, along

with Wardell Gray, Charlie Mingus and Dick Twardzik recorded there.

“He was a

policeman and a frustrated trumpet player who loved jazz,” Camacho says of

Curran. “He loved Boots. It was unbelievable what he used to do. He had the

Kenton Band up after they played in town and fed them. He was a helluva nice

guy. We used to play commercial music while people dined. Then we’d throw in a

little jazz thing once in a while. We worked at Christy’s for a couple of years

before we went into the Crystal Room.”

The Crystal Room was in the cellar of the

Sons of Italy Hall in Milford. It’s been said that if Mussulli

couldn’t tour the world, he’d bring the world to Milford. At one point in the ’50s,

Mussulli started hosting a series of jazz concerts at the hall. A partial list

of those to play the venue includes Stan Kenton, Duke Ellington, Count Basie,

Maynard Ferguson and, of course, Charlie Parker.

Camacho

says that the Boots Mussulli Quartet also worked in Boston. “A couple of times we took the

place of Herb Pomeroy at the Stables. Herb and Boots got to be good friends.

Everybody knew Boots.”

At the

Fox Lounge, Camacho played the house piano. “Can’t you tell by the recording,”

he says, laughing heartily. “It was an old upright. I’ve played many of those.

That’s what I used to have at home.

“It was

jazz. There was no dancing or anything. Boots was well known. He still is.

Being in his hometown and everything he used to get pretty good crowds. We used

to get different musicians who used to come in and sit in every once and a

while -- most of the time they were

musicians that Boots had arranged to come by — Herb Pomeroy, Dick Johnson, from

Boston.

|

| Herb Pomeroy (right) with his sax section at the Crystal Room |

When

asked about his musical training Camacho says, “I didn’t really study jazz

piano. It just came naturally. My family, being Portuguese, my father used to

play Portuguese guitar. I had three brothers. They all played regular guitars.

They used to do the old Portuguese ‘fado’ music. It’s like a blues. It’s still

popular in Portugal, but they modernized it. The

family used to get together on Sundays and my mother would sing. I started on

ukulele. My brother used to paint my face black and we would do minstrel shows

at the Elks in Hudson. We used to go to Concord Prison

too and play for the ‘con’ men.

“There

was an Italian maestro from Marlborough. He was my brother’s teacher. He

used to teach solfege. I grew up with the big bands. I got to like jazz. I liked

Kenton’s band and the swinging bands like Woody Herman.

“When I

got out of the service I went for a year or two to Berklee, which was

Schillinger House. They gave me the two books, I still got them here and I

still don’t understand them. I liked to listen to different piano players, but

there wasn’t any one special piano player at that time that I copied. I more or

less followed my own ideas.”

Drummer Joe

Andrade, Arthur’s younger brother says, “I took lessons with Boots. I had taken

some lessons here with some local musicians. Then Arthur says, ‘You got to go

with Boots.’ I was a teenager. I took lessons with Boots for two years. “As a

matter of fact, I was his last student on Thursday nights. Boots didn’t drive.

I used to bring him home after my lesson. I played alto. Boots was a very good

teacher -- as far as technique and getting your sound going. We worked on a lot

of legitimate stuff.

|

| Drummer Andrade |

“Every

lesson he would write out one of the old riffs for me. I’ve still got a stack

of hand written riffs from him. While I was playing my legitimate lesson, he

was sitting back there writing. He would just write them off the top of his

head and put them in front of me and I’d try it once or twice before I left —

‘Groovin’ High,’ and all of that stuff.

“I went

into the Navy as an alto player, not as a drummer. When I got out of the Navy,

Arthur says, ‘Joey, we need drummers.’ That’s why I got into drums.”

Arthur

was Joe’s senior by 14 years. When asked to describe his older brother, Joe

says, “To begin with, he was one of the naturally funniest people that I have

ever known in my life. He had the most beautiful personality.

“Arthur

was a legitimate drummer from the time he was a little boy. At 12 years old, he

used to go into the RKO in Boston and take lessons during the

breaks from one of the top drummers in Boston at the time. He was just a young

kid. He used to have to go in on the train by himself. Of course, my uncle

George Melo, was the lead trumpet player at the RKO at that time.”

Joe says

as good as Arthur played there were only a few years in his life where he made

music a full time job. “He worked in a shoe factory for years,” Joe says. “My

father was a foreman at Diamond Shoe in Marlborough and Arthur worked there for many

years.”

Arthur

also taught privately and at local schools, but according to his brother, he

did not like it. He also says that although Arthur had the opportunity to tour

he stayed close to home.

“He had

offers,” Joe says, “Tommy Dorsey and Toshiko Akioshi. She

wanted Arthur to go on the road. She was with Charlie Mariano at the time.

Arthur was probably the most underrated musician of his era. The last time I

played with Dick Johnson, one of the first things he said was: ‘I was just

talking with somebody about your brother.’

|

| Toshiko Akioshi |

“Arthur

was right up there with all the musicians, jazz wise. He read like a bugger.

There’s not too many of those. He was taught rudimentary drumming. In those

days everything wasn’t just fake it. You learned how to play legitimately

first. I think there are probably a lot of young drummers in our area that

tried to model their style after Arthur.”

Bassist Joe Holovnia says, “Considering the circumstances, I think the tape turned

out reasonably well. The playing on it is superb. It could have been better

acoustically, miking and all that but the playing is top notch. Boots is

absolutely fantastic.”

When

asked to riff a while on Mussulli’s playing, Holovnia says,

“First of all, he was a phenomenal alto player. He started in swing. Then when

Diz [Dizzy Gillespie] and Bird [Charlie Parker] came on the scene, he adapted

to that. He was influenced by the bebop thing and it was the way he handled it.

It amazes me today.

“Boots

knew scales upside down and backwards. He was so flexible. He certainly didn’t

play on scales. It was ideas -- a configuration of notes that make sense,

superimposed on the chord structure. He was very astute with his chord changes,

but he wasn’t just playing chords or just playing scales. He was playing ideas

based upon the chord changes. He was an absolute master of that.

|

| Serge Chaloff and Joe Holovnia |

“You

could be on stage and the whole rhythm section could fall apart and he could

just go right through you. He would do chorus after chorus and it was fresh and

constantly surprising. In other words, he’d didn’t play superfluous. He didn’t

play unnecessary notes. He wasn’t trying to impress anybody. He was playing

absolute musical ideas with full control of the swing of it, timing of it. You

could never find fluff in there. Everything he played, he played with purpose.”

Holovnia,

who is still active on the scene on both bass and piano, says in working with

Boots, “You had to be on your toes. In his mind he pretty much would already

have a set group of tunes he would use. In some cases he wouldn’t even have to

call them out. He’d start them. He’d know exactly what he was doing. He’d play

an introduction and there was no mistaking what he was doing. Sometimes he’d

just play the head to get you rolling and then let the rhythm section play for

a long while to get the section cooking. Then he’d fall in.”

By the way,

Joe Holovnia is the father of drummer Mark Holovnia, who has been touring

with the Artie Shaw Orchestra under the direction of Dick Johnson. When asked how he hooked up with Boots, Joe says, “Boots had a rehearsal big

band in the early ’50s down in Milford with guys like Red Lennox and Moe

Chachetti, Ziggy Minichello and Paul Shuba. So I got to know Boots back then.

Then sometime in the mid-’50s he, in effect, formed the quartet. We worked

pretty steadily with him maybe 10 years, until shortly before he got the

cancer.

“Most of

the playing we did with that group was out of town and not in this area. I

remember playing up in Topsfield. There was a club. We played concerts at Williams College. We played at Northeastern University. We played at the Worcester Craft Center.

“The Fox

Lounge was an institution. It was owned by a guy named Walter. He was just a

businessman who recognized what made good sense — inexpensive, stiff drinks,

good food, open-steak sandwiches.”

|

| George Shearing and Father Norman O'Connor |

Holovnia

says although no other known recording of the Boots Mussulli Quartet has

surfaced, there may be one other document of the group out there. This one

might even be in video. “We did a thing on Channel 2,” Holovnia says. “Father

Norman O’Connor, the jazz priest. We appeared on that program. We also did a

thing on, I’m not sure if it was Channel 4 or 5, the thing with Norman

O’Connor. Remember Jackie Stevens? His folks made an 8 mm film off the

television. That’s the closest thing I can think of anybody making a record of

it.”

|

| Jackie Stevens, Danny Camacho and Joe Holovnia |

At the

time of the recording, Boots was approaching 50, the elder statesman of the

group. Holovnia says, “I was maybe 33. Danny’s probably a year or two older.

Arthur was probably the same age. It won’t be long before we are all gone.

There’s only myself and Danny.”

“Boots

broke the group up a year or two before he died,” Camacho says. “He had cancer.

He was going to the hospital, a cancer center in Walpole. They found a growth near the

nape of his neck and gradually found out it had grown down his neck under his

jaw and down his throat. It came all of a sudden. At first, when he went to the

hospital, he was told they got it all out. Same old familiar story. And for a

while he was feeling pretty good. Then all of a sudden ‘bingo’ he was gone.”

Boots

died on September 23, 1967. More than forty years after his

death, his legacy as a great player, teacher and human being continues to this

day. Now, with the rediscovery of the Boots Mussulli Quartet Live at the Fox

Lounge, we have another living testament of that greatness.

|

| Boots writing |

Note: This is a work in

progress. Comments, corrections, and suggestions are always welcome at: walnutharmonicas@gmail.com. Also see: www.worcestersongs.blogspot.com Thank you.

Here’s a

clip with the Mussulli Quartet playing “Lullaby in Rhythm,” live at the Fox --

The

publicity for the show read: “America's greatest living jazz singer

will be celebrated by an impressive group of guests on this special

evening produced by Lunched Management, in collaboration with the

Jazz Foundation of America. Join us at the wonderfully intimate Joe's

Pub to honor the great Mark Murphy, who is also scheduled to

perform.”

The

publicity for the show read: “America's greatest living jazz singer

will be celebrated by an impressive group of guests on this special

evening produced by Lunched Management, in collaboration with the

Jazz Foundation of America. Join us at the wonderfully intimate Joe's

Pub to honor the great Mark Murphy, who is also scheduled to

perform.” The

singer’s influence can be heard in a variety of today’s jazz

singers including, Kurt Elling, Ian Shaw, and local singer Richard

Jarvis, who sings uncannily like Murphy, especially on tunes he

learned from the master: “Don’t Go to Strangers,” “Never Let

Me Go,” and “I Fall in Love too Easily.”

The

singer’s influence can be heard in a variety of today’s jazz

singers including, Kurt Elling, Ian Shaw, and local singer Richard

Jarvis, who sings uncannily like Murphy, especially on tunes he

learned from the master: “Don’t Go to Strangers,” “Never Let

Me Go,” and “I Fall in Love too Easily.”

.jpg)

QE9s3HG+UyBSBD60EhR!~~60_57.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)