By David "Chet" Williamson Sneade

When I first began the writing of The Jazz Worcester Real

Book, I wanted to include a collection of interviews with musicians talking

about some of the places where they had performed.

After talking with Roscoe

Blunt about the Saxtrum Club, Emil Haddad about the El Morocco, Bunny Price on

the Kitty Kat, Ken Vangel on Circe’s, among others, I quickly ran out of room. I still have all of my interviews on file and from time to time I post them.

Here’s one on the original Quinsigamond Elks Club, No. 173,

when it was on Summer Street. I called upon drummer Tom Price to fill us in. Before jumping into the Q&A, here’s a

little riff on Mr. Price: He was born on September 27, 1942. He is the son of

the late trumpeter Barney Price and brother of bassist, Bunny Price. His uncle

Billy Price, a drummer who had to stop because of ill health, first influenced

him.

|

| The Summer Street building that once housed the Elks |

Tom Price studied privately with local drummer Joe Brindizi,

Alan Dawson and George Kloss. As a teenager he formed a Calypso group with

Jamaican singer Kingsley McNeal. During high school, he appeared regularly at

the Elks Lodge – when it was on Summer Street in Worcester – with his brother

Bunny and pianist Johnny Catalozzi.

He was a student at Berklee College of Music before

receiving a BA from the University of North Carolina. Price was drafted into the military in 1960

and sent to the Naval School of Music in Washington, D.C. After his military

stint, he spent time in New York City recording and gigging with the likes of

Jaki Byard, Burton Green, Henry Grimes and Frank Wright.

For more than 30 years Price had been teaching the art of

drumming at the New Community School of Arts in Newark, NJ. He was recently

reunited with the rediscovered bassist Henry Grimes for a series of concerts in

New York.

We begin with a general interview about his life in music.

Did you come up playing drums inspired by your dad?

Price: Yes, the fact that he was a musician naturally drew me

into it. My uncle Billy Price was a drummer. I used to spend hours with him

talking about the music. He was a real encouragement and inspiration to me.”

Tom started playing drums as a child, first on hand drums – congas and bongos –

then trap drums.

Did you take lessons?

Price: I started out playing bongo drums. I taught myself

listening to Calypso music when it was the craze — listening to Harry Belafonte

and of course a lot of the other Latin bands — Prez Prado and people like that

were around. I was playing bongos and congas.

I played with Kingsley McNeal. He formed a Calypso group. He

was originally from Kingston, Jamaica. I was in my early teens, like 14 or 15.

I played with him for two years. We used to play some of the country clubs

around Worcester County. He was a singer. We had a little group with some of my

sisters. I performed with him a great number of times with just him singing and

myself playing the bongo drums. A few times he had someone on guitar.

I used to play the conga drums for Reggie [Walley] down in

his dance studio on Main Street. I even performed a few times with him at the

dances. His wife Mary choreographed these routines. That’s how I started out.

|

| Reggie Walley at the Kitty Kat |

Then I started taking lessons with a guy who played in the local symphony. I

don’t know if he is still around. Then I took lessons with Joe Brindisi. He is

still playing around. After I graduated from high school — I was at Commerce

High — I went into Berklee. I was studying with Alan Dawson. He was, I would

have to say, the major influence on me, in terms on playing. Aside from

listening to guys like Max Roach, Roy Haynes and Philly Joe Jones – you know,

listening to these guys on record.

I would like to ask you about the Elks.

Price: That was the spot. Back then it was on Summer Street not far

from Union Station. Just a little in from the square. That’s where it was for

many years – across the street from Second Baptist Church. We did sometimes

Friday and Saturday night. Sometimes it was a late afternoon on Sundays. We

played functions and dances as well.

Do you recall any of the players?

Price: Johnny Catalozzi played with us an awful lot. Bunny.

Al Pitts, the tenor player. He died. He stayed in Worcester for quite a while

then he moved into Hartford. He used to come back and forth every now and then

to play.

I heard he was quite the bluesy player.

Price: Oh, yes. He was. He was originally from Gary,

Indiana. He ended up in Massachusetts because he was in the army. He was

stationed at Fort Devens. After he got discharged he stayed around. He took up

residence in Worcester for a while. As a matter of fact, he married one of my

cousins.

|

| Tom Price |

Did you play jazz as well as the pop songs of the day?

Price: We formed a group with Art Lonegan. Bunny was on

bass. Lou, a piano player, whose name escapes me. Art used to get all these

gigs. We played the pop stuff of the day. We did weddings and commercial gigs.

At the time I was in high school. I left to go in the service when I was 22.

While I was at Berklee I was doing a lot of playing.

Do you recall what the old Elks looked like?

Price: It was basically a membership thing. It was a social

club as such. I remember the place that was at Clayton St. We had a little club

there for a while. I know my dad and Howie played there. I’m trying to recall

if it was still the Saxtrum at that time. It may have been the tail end of the

Saxtrum Club that I am thinking of. It didn’t last. Later on it became a

church.

|

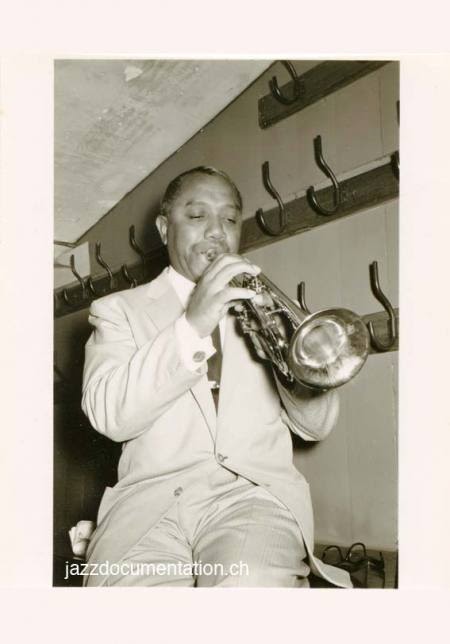

| Jaki Byard blowin' tenor |

Did Jaki Byard play there?

Price: I didn’t play with Jaki in Worcester. I played with

him in New York. We played at the Top of the Gate. That was during the days when

I was hanging out in the city. That was a gas. It was really great to play with

Jaki. It was a quartet.

Did you gig with Howie Jefferson?

Price: We did some things in that little place I was

describing. It was another thing they had going. I don’t want to say it was a

rival to the Elks. I did a few things there with Howard and my dad. We had

different people on piano. Judy Wade played bass. The Elks was there for quite

a long time. It was pretty much the focus in terms of black entertainment. It was

the place for many, many years. That’s where everybody came on Friday and

Saturday nights. There was an upstairs and downstairs but downstairs was where

we did all the playing. It was a big boxy room with tables. I remember playing

a gig upstairs too.

Did you feel like it was a learning time for you? A time to

pay your dues?

|

| Freddie Bates and the Nite Hawks |

Price: Definitely. It was a learning and growing time for

me. Just to get the experience to play. For me the Elks was the place. It was a

mentoring time. As far as some of the older black musicians that were around. I

remember Freddie Bates. He had a stroke, but he was always around at sessions.

They were role models. A lot of it wasn’t spoken out to you directly. You just

learned. You noticed how people dressed and how they came to the gig and things

like that. You were expected to be there on time and all of that. I did a lot

of watching. Because even before I got to play somewhat regularly, I was at

gigs just watching, observing and learning that way.

|

| Tom Price, Henry Grimes and Perry Robinson |

Price’s Discography: Burton Green Quartet, Henry Grimes,

Henry Grimes Trio, The Call, Patty Waters Sings, and The Frank

Wright Trio

|

| Henry Grimes, The Call |

Press Quotes: “From the first few notes I was destroyed, clarinetist

Perry Robinson, and drummer Tom Price are amazing.” – Michael Fitzgerald, in a

review of the Henry Grimes album The Call.

Touring and other highlights: Played with Jackie Wilson at

Mechanics Hall, appeared at the Village Vanguard, the Village Gate and the

Newport Jazz Festival.

Sections of this piece were drawn from The Jazz Worcester Real Book and an interview with Tom Price conducted in 2007.

Note: This is a work in progress. Comments, corrections, and

suggestions are always welcome at: walnutharmonicas@gmail.com. Also see:

www.worcestersongs.blogspot.com Thank

you.

.jpg)

.jpg)