By David "Chet" Williamson Sneade

Trumpeter Elwood Barney Price Sr., died in 1989

at the age of 76. The following is an unpublished feature that I wrote in 1987,

a couple of years before his passing, as an English assignment in college.

Robert Walker, my English professor at Worcester State, asked us to write an

extended piece that we could then pitch to the Worcester Telegram and Gazette.

The trumpet shall sound,

And the dead shall be raised incorruptible,

And we shall be changed.

-- Prophet Isaiah, Old Testament

Elwood “Barney” Price is sitting with his

trumpet in his lap in the first pew waiting for his call to play. On this

Sunday, the service is for children. The children’s choir is featured once a

month here at the A.M.E. Zion Baptist Church on Belmont Street. Mr. Price is

usually asked to play on the hymns, his favorite.

It’s a crisp autumn day, the leaves are turning,

and at 75, the trumpeter has much to consider in his reflection. Although a

1986 heart attack, and a continuing bout with diabetes have slowed Price, his

love for playing the trumpet is still with him. He was born in Worcester on

February 17, 1913. As a young child he went to Belmont Community School and is

a graduate of Commerce High School, class of 1932. Price played in the high

school band and while still a teenager he began to perform professionally.

After church, I introduce myself and ask for an

interview. He says, “Sure, why don’t we meet at my place in an hour. I live at

53 Catherine Street. See you there.” Price lives with his wife, Muriel in a

three-decker, not far from Green Hill Park. The couple raised nine children,

six boys and three girls, all grown and on their own. We take a seat at the

kitchen table.

“Can I get you a drink?” he asks, before

reconsidering what he said. He laughs and says, “Maybe I should rephrase that.

You are probably not even old enough to drink. Can I get you a soda, water, or

a cup of coffee?”

|

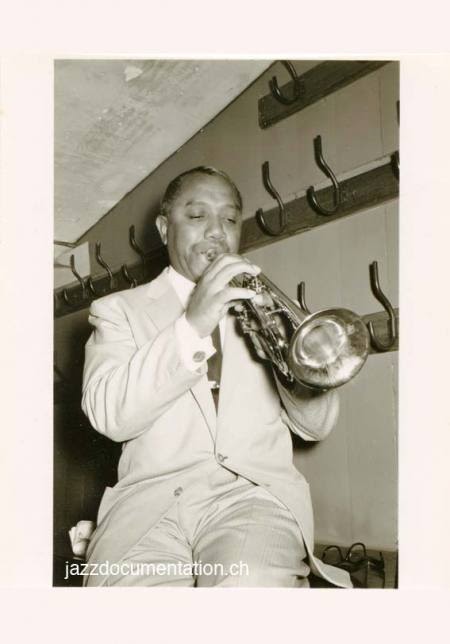

| Wendell Culley |

Mr. Price’s memory reaches way back. I break the

ice by asking him how he began playing. He says as a child he wanted a clarinet

until he heard the records of Louis Armstrong.

“My mother bought that first trumpet for me for

Christmas,” Price says. “I was 13. An Armenian kid from the neighborhood showed

me the fingering for ‘Oh, Come All Ye Faithful.’ That was 60-odd years ago and

that wasn’t just yesterday. And you know the best thing about it is Wendell

Culley, one of the best trumpet players around – who was playing with Count

Basie, a black cat from Worcester – broke it in. He came home for the holidays.

“I don’t know how he knew I had a horn. I was

playing it on Christmas day and he came to my house that night and wanted to

borrow my horn. I said, ‘Geez, I haven’t played it myself yet.’ But I knew he

was a good guy. Yeah, Wendell Culley broke in that horn of mine and I’m glad he

did because I’ve been playing ever since.”

Price says soon after, his mother sent him to

the basement to practice. He is said to have been so proud of his trumpet that

he carried it everywhere he went and attempted to play everything that he

heard. Price said that a bandmaster to a local brass band took a “liking to me

and taught me music.”

He also studied with Charlie Bowles. “He was a

great trumpet player,” Price says. “I studied privately with him. He played the

theater circuit. He played the Palace. We used the Aubin Method. It had

everything you wanted to know about the trumpet in that book. I think I still

got it. It’s a good method today.”

Price was first inspired by the trumpet sound of

Louis Armstrong and later Joe Smith, Doc Cheatham, Henry “Red” Allen, Charlie

Shavers, and Jonah Jones. I asked him about the influence of Armstrong.

“Louie Armstrong? He was the first one that

really stunned me,” Price says. “I was coming down the hill from high school

one day and see the sign that said: Louis Armstrong. He appeared at Mechanics

Hall. This was around 1930. He had that record out, ‘Shine.” He had 10-12 men

with him. Amazing.”

|

| Guido Grandpetro (alto), Howie Jefferson, possibly Jaki Byard on piano, Barney Pice singing |

One of the trumpeter’s best friends in life was

Howie Jefferson. The late saxophonist, who died in 1981, was one of the more

popular musicians ever to come out of the Worcester area. He and Price were

neighbors in the Laurel-Clayton section of Worcester. I asked Mr. Price to riff

awhile on his friend.

“I got my horn for Christmas and Howard got his

the following March,” he says. “I couldn’t write the rhythms see so, he’d play

a note and I’d write it down. One of the first tunes we got down was a Duke

Ellington thing, I think it was ‘The Mooche,’ (the trumpeter sings a phrase of

the tune).

“My folks always had records around the house.

My mother’s brother was a drummer. He went on gigs with Fats Waller, but like

all musicians he had family trouble. He left his family in Boston. They say he

was a good drummer.

“Howard’s mother would buy a lot of records and

we’d take a lot of stuff off the records. … ‘Black and Tan’ by Duke. See, we’d

play those songs all day. Guys used to ask, ‘Where’d you learn that at?’ They

didn’t know we had our own arrangement. Howard couldn’t write at all, but he

could play anything under the sun. I’d come home from school and the first

thing I did was go to Howard’s house and play and listen to records. We played

even after we got married.

“Howard had a wonderful ear. He was one of those

guys that could hear anything and then play it. He was playing somewhere and he

was playing ‘Body and Soul’ and blew Coleman Hawkins solo note for note and

never did he see that song on paper.”

By the time he was 17, Price was playing

professionally with Boots Wards’ Nite Hawks, one of the city’s first and best

jazz bands. In a 1929-‘30 black and white publicity photograph of the Nite

Hawks stands Price looking rather dapper. To his left and right, other members

of this all-black band flank him, including Jefferson. The men are gathered

around bandleader and drummer Ward, who sits behind an archaic drumkit with one

hand held to his heart, the other raised to the heavens. In front of the

eight-member ensemble is an impressive display of the group’s musical

instruments.

At a quick glance the picture could be mistaken

for one of King Oliver, Sidney Bechet, Jelly Roll Morton or any of the other

great New Orleans bands of the 1920s. The Nite Hawks were from Worcester. In

1929, the year that marked the beginning of America’s Great Depression, the

Nite Hawks appear to be a happy bunch. Dressed in tuxedos, yet casual in their

stance, and wearing smiles.

|

| Howie Jefferson at far left. Price is standing behind Ward, the drummer. |

“We had some great times,” Price says. “Yeah, we

were very lucky. We travel around. We played all over New England. We might be

in Providence tonight. Springfield tomorrow. We were an all-black band of

Worcester boys. This was before WWII broke.”

The Nite Hawks played their music at private

parties, community centers, social functions, and weddings – anywhere and

everywhere. There were no so called “jazz” nightclubs in Worcester.

“We mostly played for dancing. One summer, we

played at someplace down on Shrewsbury St. All the guys were ‘shocking’ the

girls out there. Man, I thought that was great,” Price said, chuckling.

|

| Jefferson seated at right of Ward holding alto and Price is standing next to the banjo player holding his trumpet. |

Price said, Boots was the bandleader and a

pretty good drummer for them days. “He could sing too. He’d sing tunes like

‘Old Rockin’ Chair,’ he says, leaning back in his chair and singing a few bars

of the tune with a dreamy, faraway look in his eyes.

When Boots Ward died Freddie Bates, the tenor

saxophonist in the band, took over the role as leader. “Freddie was a good

player but he wasn’t a ‘take-off’ [soloist] man,” Price recalls. I know that

sounds funny for a black cat, but he’d let others do that. He’d sit there and

read the stuff all night.”

Price and Jefferson stayed with the Nite Hawks

for almost 10 years, but as the music scene changed and they progressed, they

began to look for work elsewhere. Both musicians were given opportunities to

leave the area and tour with popular jazz bands of the 1940s and ‘50s, however

the two friends chose to remain in Worcester close to family and friends.

Price and Jefferson were founding members of the

Saxtrum Club, a fraternal organization and one of the first jazz collectives

founded by musicians in New England. It opened in 1938 at the corner of Glen

and Clayton Streets. The first group included Price, Jefferson, saxophonists

Dick Murray and Ralph Briscott, pianist Jaki Byard, drummer Eddie Shamgochian,

and bassist Harold Black.

|

| Officers of the Saxtrum Club in 1940. The date tagged is wrong. Price stands in the middle. Jefferson at far left next to Alice Price. Jaki Byard is seated at far right. |

“We named it the Saxtrum Club –

Sax(ophone)-Trum(pet),” Price says. “I was the secretary and treasurer. We were

only paying $12 a month for the store. We had two rooms. There was a tailor

next door, but they were closed at night. We had it together for a good ten

years.”

Some of Worcester’s finest musicians hung out at

the Saxtrum Club, ones who went on to become established performers, including

pianists Barbara Carroll, Don Asher, and John “Jaki” Byard, Jr.

“Young Jaki Byard, from the neighborhood, would

hang out there all day,” Price says. “There were a lot of cats from downtown

who used to come and blow. I sanctioned pianist Don Asher for the Union. He

went on to write the Hampton Hawes [Raise Up Off Me] book. He played the

Valhalla with us.”

|

| Guido Grandpetro, unidentified drummer, Jefferson, Price, unidentified singer, and Don Asher at piano. |

Word of the night jazz jam session got out and

soon jazz musicians on the national scene would fly by the Saxtrum Club to

play. At same time, the Plymouth Theater in downtown Worcester featured some of

the biggest names in show business. After hours, they would go to the Saxtrum

and jam with the local musicians.

“We had them all down there,” Price says. “Anita

O’Day, Roy Eldridge, Chu Berry. Jammin’ with those guys, man, it was a

privilege, because those cats knew what they was [sic] doing. These cats would

come in off the road and say, ‘Let’s play something we can blow on.’ If they

played 100 choruses of ‘How High the Moon,’ ain’t nobody said nothing.

“Gene Krupa was in town one night with Roy

Eldridge in the band. They wanted to stay till 3-4 o’clock in the morning. We

stayed as long as we could. The cop that was on the beat was a good cop. He’d

say just shut the windows and the doors. They were really good like that. We

had some good times and when you think of it now – nobody taped that stuff.”

At 21, Price went to work for the railroad.

“That was at Union Station,” he says. “I stayed

there 25 years. I was there through the war years. One good thing about it was

I could always get off in time to work a music job. I had two boys and I got to

support them somehow. I was married when I was 19, so I said I’ll go to work. I

wasn’t much for running around anyhow.”

Price held various positions for the New York

Central and later, the Pennsylvania Central Railroads from 1936-1960. In 1960,

he joined the Worcester County National Bank as a public assistance officer, a

job from which he retired in 1978.

Throughout his working life, somehow Price

always found time to play music. He has been a member of Local 143, Worcester

Musicians Association. The weekly session is something Price has also

participated in since the Saxtrum days. In the 1960s the jam was held at the

Fox Lounge on Rte. 9, Westboro, then at Reggie’s Kitty Kat on Main St. When

Walley moved to Austin St. and opened the Hottentotte in the 1970s, Price

attended jam sessions held there. Sessions were later also held at the Elks

Lodge on Chandler St. until the club underwent renovations in 1987. Price was there.

|

| Barney Price and Edwin Perry |

Price also began working with longtime friend

Reggie Walley in a group called the Soul Jazz Quintet. The SJQ also featured

saxophonist Nat Simpkins, pianist Allan Mueller and Barney’s son, Elwood Jr.,

“Bunny” Price on bass. Bunny started on trumpet like his father and made the

transition to bass out of necessity. Good bass players are hard to find.

One of Barney’s other sons, Tommy, is also a

musician. “Tommy is a drummer who studied with Alan Dawson in Boston,” Barney

says. “He’s a teacher now down in New Jersey. He still plays out though. He and

Bunny were the only two boys out of my six who wanted to be musicians.”

Tommy Price, who recorded extensively throughout

the 1960s with artists such as Henry Grimes and Frank Wright for the ESP label,

is still active and recently recorded with Ernie Edwards. The Sunday afternoon

session at the Elks turned out to be the last regular job for Price and his

last public gig with the Soul Jazz Quartet at the GAR Hall as part of the First

Night celebration last New Year’s Eve.

These days, Price can be found Sundays in the

first pew in the African Methodist Zion Church on Belmont St., where he

performs with the church organist and choir. He plays old gospel hymns such as

“Pass Me Not, Oh Gentle Savior,” “How Great Thou Art” and “Just a Closer Walk

with Thee,” a tune he often played with boyhood friend Howard Jefferson. It was

one of the last tunes they played together before Jefferson died.

As a jazz musician, Price is a melodic player

who never veers far from the blues. His gentle side can best be heard on his

phrasing of such ballads as “Georgia” or “Bye Bye Blackbird.” His big brassy

sound is heard on standards like “I’ll Remember April.” His blues side can be

heard on “St. Louis Blues” or “Red Top.”

“You’ve never lived, until you’ve danced to the

Louis Armstrong-styled Price trumpet,” T&G writer Jack Tubert once wrote.

“Soft and oh, so tasty.”

Price once told Worcester T&G writer Susan

Seymour that to play jazz -- “You got to have that feeling … I’ve played with

certain black guys and they just didn’t have it. They didn’t know how to bend a

note. Real jazz, it just comes up like a cuppa coffee boiling over.”

I asked Mr. Price if he had any advice for young

players. He said, “Learn how to play the piano. It’s all there in front of you.

One thing that people had the wrong idea about. People think you have to play

loud to play jazz. Play pretty. Also, get out and hear music live. My wife and

I used to go to New York all the time. Small’s Paradise and uptown. We saw

everybody man.”

|

| Elwood "Barney" Price, Sr., and Elwood "Bunny" Price, Jr. |

Addendum

Price died on December 3, 1989. In addition to

his nine children, he left 35 grandchildren, and 42 great-grandchildren. Though

his joyous trumpet sound was never recorded, Price left a local legacy in jazz

that should not be forgotten.

Note: This

is a work in progress. Comments, corrections, and suggestions are always

welcome at: walnutharmonicas@gmail.com. Also see:

www.worcestersongs.blogspot.com Thank

you.

.jpg)

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

ReplyDeleteWorcester dj services