By David "Chet" Williamson Sneade

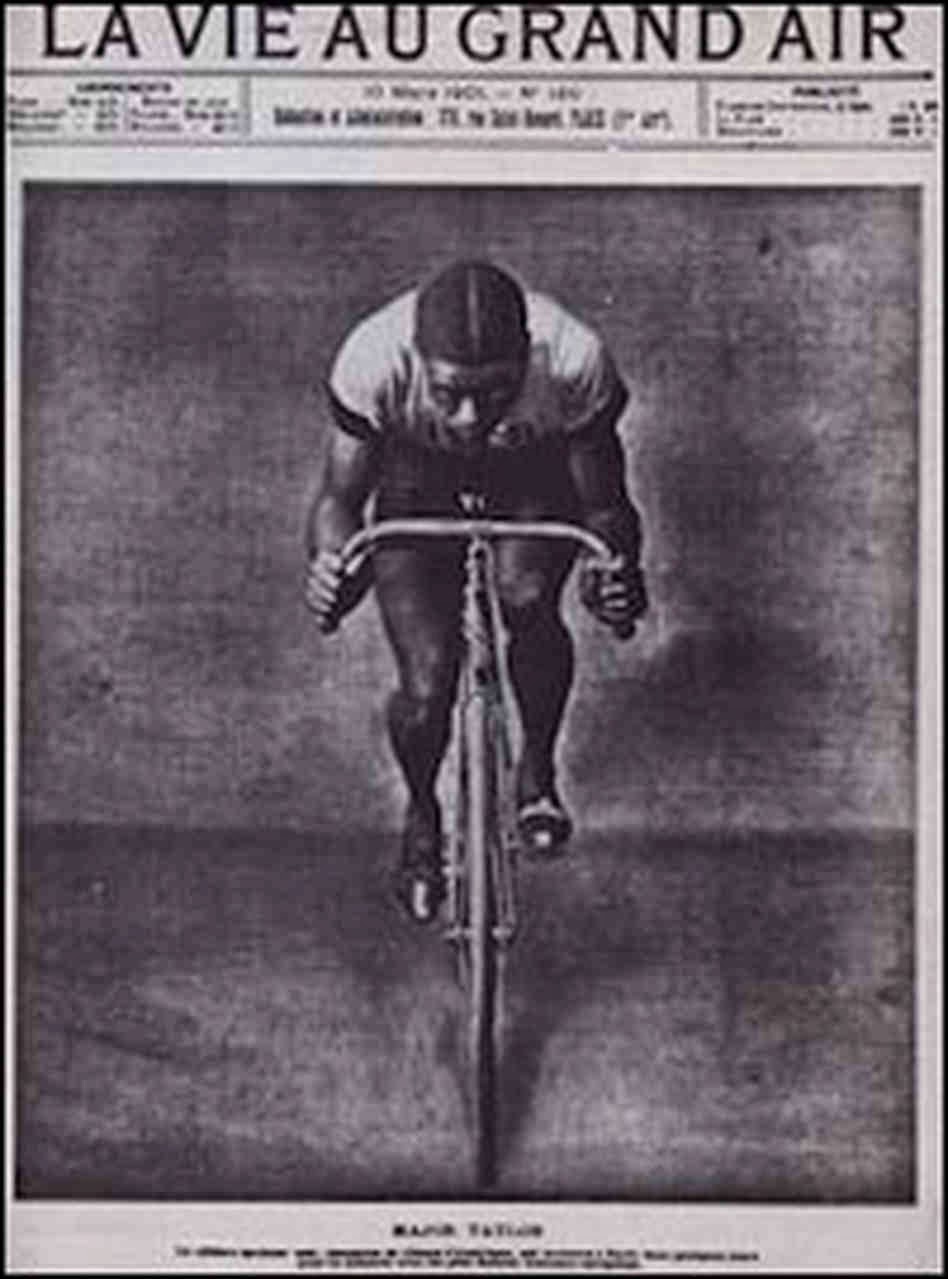

He was known as the “Black Cyclone” and the “Worcester Whirlwind.”

He was Marshall “Major” Taylor, a three-time world champion cyclist and one of

the first Black American champions in any American sport.

He was also a musician who may have played ragtime in the

pre-jazz era. Taylor sang and played both the mandolin and piano and received

his nickname in a band setting. This item ran in the February 21, 1900 edition

of the Worcester Daily Telegram: “Marshall Taylor is his real name, but Major

he has been ever since he was a 10-year old boy at school, he wielded a baton

in front of a juvenile band.”

Taylor was born on November 26, 1878 in rural Indiana and

raised in Indianapolis, but he became a champion in Worcester. His life was one

of great triumphant and equal tragedy. He died penniless in Chicago on June 28,

1932.

His story is well documented. There are a collection of books,

numerous articles, and websites dedicated to his greatness. Here in Worcester,

a handsome statue of his likeness stands outside the library, a street has been

named after him, and annual cycling events happen in his honor.

Little is known about his musical life. What we do know is that

in his downtime, he liked to play music. At one point – at the height of his

championship reign -- Taylor used his fame to enter vaudeville.

In his landmark book, Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career

of a Champion Bicycle Racer author Andrew Ritchie wrote about this experience.

“There was talk of Taylor going after more motor-paced records, benefiting from

his end-of-season strength and fitness to attack the prestigious 1-mile world

record, as he had done at the end of 1898 and 1899. But instead of undertaking

the stress and strain of more record breaking, Taylor embarked on a new career.

Capitalizing on his success and fame as champion of America, he decided to go

into vaudeville."

In his landmark book, Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career

of a Champion Bicycle Racer author Andrew Ritchie wrote about this experience.

“There was talk of Taylor going after more motor-paced records, benefiting from

his end-of-season strength and fitness to attack the prestigious 1-mile world

record, as he had done at the end of 1898 and 1899. But instead of undertaking

the stress and strain of more record breaking, Taylor embarked on a new career.

Capitalizing on his success and fame as champion of America, he decided to go

into vaudeville."

Ritchie notes that vaudeville was the popular entertainment of

the day and part of Taylor’s everyday experience. The writer says that the cyclist had a

fine singing voice and like other athletes before him, he would have been quite

the novelty on stage.

Unfortunately, he did not get to share his piano playing with

vaudeville audiences. As Ritchie says, Taylor was a bicycle racer after

all and that in itself made him a popular entertainer. The cyclist was contracted by local agent Charles Culver, the manager of the Worcester Coliseum on Shrewsbury

Street. Instead of a musical performance, Taylor agreed to ride a stationary

bike known as ‘home trainer,’ a kind of treadmill for cyclists. He was to

compete against one of his rivals, the famous Charlie ‘Mile-a-Minute’ Murphy,”

who is credited with – as his name implies -- being the first cyclist to ride a

mile in one minute's time.

|

| Worcester Daily Telegram, 1901 |

Ritchie picks up the action: “Home trainers were set up

alongside each other on the stage of a theater and connected to big dials,

which showed the distance the two riders had covered by means of two big

arrows. The machines were splendidly set up on stage, decorated with flags. With

firing of a pistol, the race began, the two men pedaling furiously, while the

audience followed the sprinting in front of the roaring, cheering crowd.

“Culver thought the act would be an instant hit, and he was

right. When it opened at the Park Theater in Worcester at the end of October,

sandwiched between comedy routines, acrobatics, song and dance acts, and moving

pictures, it was an instant success. The audience ‘cheered until it was hoarse

as the race progressed,’ reported the Worcester Telegram, ‘bursting into wild

enthusiasm when the dial at the rear of the stage showed the riders’ progress,

and one followed them as they moved around the circle with as much interest as

one would riders on a race track.’"

Ritchie says that from Worcester, this unusual vaudeville team

played to packed houses in Pittsfield, Springfield, Hartford, and other cities

and towns throughout New England.

Ritchie says that from Worcester, this unusual vaudeville team

played to packed houses in Pittsfield, Springfield, Hartford, and other cities

and towns throughout New England.

“Taylor also rode a mile on his home trainer in the window of

a Hartford bicycle dealer’s shop in the record time of 43½ seconds, a speed

equivalent to 82.5 mph. A crowd of more than a thousand people watched him,”

Ritchie says. “Having established the success of the act, Culver contracted

with Keith’s Theater in Boston for the two cyclists to appear nightly on the

Boston stage, and the home trainer races continued throughout December and

January. Keith was perhaps the most famous vaudeville company on the East

Coast, and it was they who pioneered the idea of a continuous, revolving

performance, which the audience could enter and leaved as they pleased.”

Taylor traveled to Europe and Australia to compete for his

world championships. In 1901, he spent four months in France, from March to

June, which as Ritchie says, “proved to be the climax of his athletic career.

At the zenith of his physical strength and international popularity, he arrived

in France at the culmination of a long period of rumors and promises of his

imminent coming. Promoters and spectators were hungry for the new sensation.

There would be something magical about the first visit, something that gripped

the public imagination. …

“One evening, the entire staff of L’Auto-Velo took him to the

circus to see ‘Little Chocolate,’ the clown, the only other famous black person

in Paris at the time. ‘Chocolate’ referred to Taylor’s presence during his

performance, and all eyes in the theater were turned towards the box where

Taylor sat, enjoying himself immensely.”

.jpg) This celebrity status was two decades before black American

entertainers, such as dancer Josephine Baker and jazz musician Sidney Bechet,

became the darlings of the French.

This celebrity status was two decades before black American

entertainers, such as dancer Josephine Baker and jazz musician Sidney Bechet,

became the darlings of the French.

Ritchie says when “not training, or giving interviews at

his hotel, or visiting the sights of Paris, Taylor read and wrote letters or

played the piano or mandolin. He was also a keen photographer and took pictures

with the portable Kodak he had brought with him from the United States.”

In their book, Major Taylor: The Inspiring Story of a Black

Cyclist, Conrad and Terry Kerber say that the champion cyclist, was a somewhat

frustrated musician. Quoting a French newspaper article of the day, the Kerbers

state that the cyclist was a self-taught pianist, who “because of his hectic schedule,

hadn’t found the time to play [the piano] as often as he had wished.” Taylor

was staying at the Malesherbes Hotel and in the lobby was a beautiful black

Steinway piano.

The writers also add that on one particular night he was “in a

melodious mood, he drew up a vacant stool, set his bowler hat on top of the

piano and sat down. Initially a small crowd noticed and gathered around him.

Taylor played tentatively. The small crowd grew. Warming to the gathering,

Taylor started singing “Hullo My Baby,” an American song made popular during

the 1900 Paris Expo. The crowd joined in.

"One journalist, who was present at the gathering said that he

had a 'remarkable singing voice.' Taylor’s hands poured across the piano, feet

stomping on the pedals, voice wafting throughout the room. Champagne was

brought out, and people listened and sang and slurped.”

“Hello, Ma Baby,” is an interesting choice for Taylor to sing.

It’s not really a piece of ragtime music, although it refers to the popular

music of that time: “Hello! ma baby, Hello! ma honey, Hello! ma ragtime gal.” The song was actually written by the

Tin Pan Alley team of Joseph E. Howard and Ida Emerson in 1899. It also harks

back to an early time, the Minstrel-era and the derogatory styling known as

“coon songs.”

The song, first recorded by Arthur Collins on Edison, is said

to be the first tune of its kind that refers to the newly invented device, the

telephone. The chorus refrain is complete with: Send me a kiss by wire / Baby,

ma heart's on fire! / If you refuse me / Honey, you'll lose me / Then you'll be

left alone / Oh, baby, telephone / And tell me I'm your own!”

According to Wikipedia, the chorus is “far better known than

its verse, as the introductory song in the famous Warner Bros. cartoon One

Froggy Evening (1955), sung by the character later dubbed Michigan J. Frog and

high-stepping in the style of Bert Williams.”

|

| Scott Joplin |

Needless to say, Ragtime this is not. Artistically, this is a

long way from say, Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag,” the composition that launched ragtime's popularity in 1899.

As for Taylor playing ragtime piano, no record exists.

However, it is conceivable and most probable that a proud African-American,

would have played the most popular and artistic black art-form of the day.

Worcester

As mentioned, much has been written of Taylor’s life in

Worcester. He moved here in the fall of 1895 when he was only 15. He relocated

from his native Indianapolis with his employer, Louis “Birdie” Munger, a

bicycle maker and racing enthusiast who opened the Worcester Cycling

Manufacturing Company.

The Worcester Daily Telegram reported that soon after his

arrival the young cyclist competed in a race presented by the newspaper. “After

winning the Telegram race, Major Taylor’s fame increased rapidly,” a reporter noted.

Coming to Worcester turned out to be the right move at the

right time for Taylor. In his autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the

World, Taylor wrote: “I was in Worcester only a very short time before I

realized that there was no such race prejudice existing among the bicycle

riders there as I had experienced in Indianapolis. When I realized I would have

a fair chance to compete against them in races I took on a new lease of life,

and when I learned that I could join the YMCA in Worcester, I was please beyond

expression. … It did not take me very long to get acquainted in Worcester, especially

when its riders discovered that I owned a fine, light, racing wheel on which I

could ride with the best of them.

“I shall always be grateful to Worcester as I am firmly

convinced that I would shortly have dropped riding, owing to the disagreeable incidents

that befell my lot while riding in and around Indianapolis, where it not for

the cordial manner in which the people received me.”

|

| Mrs. Taylor, Major and daughter Sydney |

Taylor not only lived and trained here, he married, raised a

child, and purchased a home in Worcester, at 2 Hobson Ave. He was a member of the John

Street Baptist Church and when not traveling, the champion cyclist, worked a

variety of jobs in addition to being employed by Munger.

He first became champion at 21. He was out of racing by 1910

at the age of 32. His decline was as steep as George Street hill.

Local writer Albert Southwick chronicled Taylor’s slide: “He

invested $15,000 in a business venture that flopped. He tried to enter

Worcester Polytechnic Institute to study engineering, but was turned down,

ostensibly because he had no high school degree.

“Then his health began to give way. He may have had an

enlarged heart from all those years of training. In the 1920s, he came down

with shingles, a painful, debilitating disease. With no steady income, he was

forced to sell off his wife’s jewelry and other items that he had purchased in

better times. Finally he had to sell their home on Hobson Avenue and they moved

into a modest apartment on Blossom Street.”

Southwick also reported that Mrs. Taylor, who had come from an

educated family, “went to work as a seamstress. Gradually she became estranged

from Taylor, as did [daughter] Sydney. [His] final energies went into his autobiography,

which he published at his own expense under the title The Fastest Bicycle Rider

in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success

Against Great Odds. It is a long, rambling book, filled with details of

individual races. It does not tell enough about Major Taylor, the man.”

The book was first printed in Worcester by Wormley Publishing. It is dedicated to his former trainer and employer, Louis Munger. In its forward,

Taylor wrote: “I am writing my memoirs, however, in the spirit of calculated to

solicit simple justice, equal rights, and a square deal for the posterity of my

down-trodden but brave people, not only in athletic games and sports, but in

every honorable game of human endeavor.”

Continuing to describe the champion’s demise, Southwick says

that while ill and broke, “Taylor went from door to door selling his book. His

wife, unable to stand the strain any longer, left Worcester and went to New

York. She never saw him again. In 1930, he too, left Worcester and headed for

Chicago, his car filled with copies of his book. In Chicago, he live at the

YMCA, from which he went forth every day to peddle his autobiography.

Taylor died on June 21, 1932, in the charity ward of Cook

County Hospital. He is buried in a pauper’s section of the Mount Glennwood

Cemetery. He was 54. According to Southwick, The Chicago Defender, a black

newspaper, was the only one to note the Worcester Whirlwind’s death.

Note: This is a work in progress. Comments, corrections, and suggestions are always welcome at: walnutharmonicas@gmail.com. . Also see: www.worcestersongs.blogspot.com Thank you.

Resources

.jpg)

Great research. This is such a sad story.

ReplyDelete